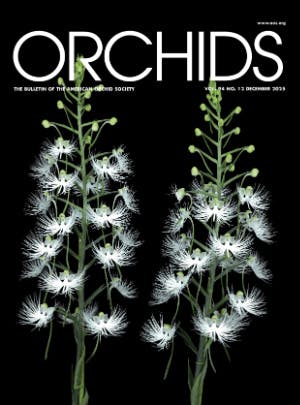

IN LATE AUGUST and early September 2024, a small group of intrepid orchid fanatics traveled to remote parts of central Brazil to visit the habitat of Cattleya nobilior f. amaliae and see wild specimens blooming. After seeing dozens of blooming C. nobilior f. amaliae (and other orchids), we then traveled south by car to visit the habitat of about six species of rupiculous Cattleya, most of which were blooming at the time. Our trip will be recounted in a two-part series, with the first part exploring the C. nobilior f. amaliae habitat and the second part discussing what we encountered in the rupiculous Cattleya habitat.

[1] Cattleya nobilior f. amaliae showing off its flower and roots in situ. Photograph by Stephen Van Kampen-Lewis.

The first and third authors, and Meaghan Gormin-Maupin left Texas and arrived in São Paulo. We immediately hopped on another flight to Brasilia (the capital of Brazil) and joined our friend Francisco Miranda and his longtime friend Mauricio Verboonen (owner of Orquidario Binot, established in 1870). From there, we got into Verboonen’s car and drove north toward the small town of Taguatinga, in the State of Tocantins. The type locality for C. nobilior f. amaliae is Taguatinga, so we will not get much more specific than that with regards to where exactly we traveled. Poaching of this rare species is a problem! It is worth noting that the “tipo” or “Matogrosso” form of C. nobilior (taxonomically C. nobilior f. nobilior) occurs southwest of this area and within a disjunct population found in the Brazilian states of Mato Grosso do Sul and Mato Grosso(Lima 2004).

[2] Drone photograph of stunning Cattleya nobilior f. amaliae perched high up in a tree.

Cattleya nobilior f. amaliae grows within a very narrow, north–south-oriented strip of “cerrado” (tropical savannah ecosystem that experiences a prolonged dry season) within a valley sandwiched between the Planalto Central (Central Highland) and Serra Geral (General Mountain Range) (Miranda 1995). This area is very rural and mountainous, with deeply incised river valleys creating rapid elevation changes. Moreover, the geology is variable, and we saw granite, limestone and basalt mountains all in close proximity. The rapid elevation changes and variable geology (which creates different types of soils) mean this is a region with significant ecosystem diversity, microclimates and variable plant communities. Cattleya nobilior f. amaliae is very specific in its preference for tree hosts (likely only growing on a few species), appears to grow within a limited elevation range and grows only in deciduous woodlands; not easy to find even if you are in the correct geographic area. Luckily, Miranda was our guide, and he has visited this region many times over the decades, specifically to find this species. While Miranda has spent recent decades in Florida, he was born and raised in Brazil and is a trained plant taxonomist with a focus on Brazilian orchids.

[3] View of the tablelands rising above the valley hosting Cattleya nobilior f. amaliae habitat.

As we left our hotel, we were all noticeably excited! We drove into the bush and quickly lost any cell signal; only guided by Miranda’s memory of the region, in which he had not traveled for close to 15 years! The maze of dusty farm roads leading to unknown mountain tops and hidden valleys seemed to stretch forever. Finding these plants is not easy, and getting lost is a real possibility. Moreover, C. nobilior f. amaliae inhabits a region known for its intense dry season, and we had arrived during a severe drought. The humidity was about 20 percent each day (personal observations), the very occasional passing car (there were not many) created a dust cloud behind it and it seemed like the whole region was clouded in smoke as countless wildfires burned unabated with no human intervention. Certainly not the conditions where you expect to find epiphytes, and we may have gotten a little turned around at one point, taking the scenic route.

[4] Only a handful of these Cattleya nobilior f. amaliae were low-growing and easily accessible. Note the naturally pendent habit of the inflorescence.

The first epiphytes we encountered were not cattleyas or even their relatives. We drove past some cattle pastures and saw the leafless pseudobulbs of a Catasetum clinging to the side of a palm tree with two seed capsules. It was great to see a member of the first author’s favorite genus! His excitement was quickly overwhelmed when we noticed a massive Cyrtopodium saintlegerianum in full bloom, entirely encircling its host palm tree. We ended up seeing many such sights throughout this part of the trip. In fact, the blooming Cyrt. saintlegerianum on palm trees in cleared fields were easily seen from a half-mile (0.8 km) away or more! At one point, Miranda flew a brand-new drone out to one of these distant Cyrtopodium plants and got some amazing photographs and video of several specimens in full bloom on the same palm. We also encountered some likely Polystachya species, though they were not blooming. Miranda indicated that they might be undescribed because no one pays much attention to this genus in this part of Brazil.

[5] One of the first orchids encountered was Cyrtopodium saintlegerianum growing on a palm tree, as pointed out by Stephen Van Kampen-Lewis.

After some time, we saw our first blooming C. nobilior f. amaliae, though the flowers were spent and starting to dry up. However, the massive root system was very apparent, and it is clear this species expends a lot of energy on this part of its anatomy. The Americans were happy, but Miranda was getting frustrated at the lack of plants encountered during our tour of the scenic route taking us to his favorite C. nobilior f. amaliae locality. We ended up seeing another C. nobilior f. amaliae, this time in full bloom but 20 feet (6 m) up in a tree. We only got to see the bottom of the flowers, but even that was exciting for some of us!

[6] Prime Cattleya nobilior f. amaliae habitat during the dry season. These stunted trees were covered in all age classes of the species.

After lunch, we drove around a country road corner and looked up a very large hill, which got Miranda very excited. We had finally found his favorite C. nobilior f. amaliae locality. Epiphytic orchids occur in lush jungles in the minds of most people, so when people see photographs of this location, they are usually flabbergasted! The trees are short, no larger than an apple tree, and spaced far apart from one another. They were totally leafless, and the area looked like it had not experienced a drop of rain in many months. The grass had also died long ago, with almost no chlorophyll visible anywhere. Still, after allowing our eyes to adjust to the blazing sun and letting the dust cloud from the car pass, we started seeing more and more pops of light pink in the “trees.” We were surrounded by C. nobilior f. amaliae! We encountered all age classes, from very small juveniles to massive clumps putting out seed capsules and flower spikes at the same time. Despite the intense drought, low humidity and constant fires, these plants were thriving. Their leaves were brown due to unrelenting sun and had deeply desiccated pseudobulbs due to lack of water, but this is a species well-adapted to such conditions. Seeing all age classes meant that population recruitment was active and that this locality was healthy. The enormous root systems on so many of the mature plants radiated out in all directions, covering more than 30 linear feet (9.16 m) of the host tree.

[7] Robust Cattleya nobilior f. amaliae with numerous seed capsules and buds about to open. Note the brown leaves, shriveled pseudobulbs and exposed position on the tree. All typical of this species during the dry season.

Next, we visited some areas that Miranda had not previously investigated for C. nobilior f. amaliae. Instead of a forested area, we were searching the remaining trees in otherwise cleared cattle pasture. It turns out that these giant, old trees were absolutely dripping in C. nobilior f. amaliae. We saw enormous plants that could be 3–4 feet (0.9–1.2 m) across and were likely very old plants, considering how slowly this species grows. Also, we could see absolutely stunning flowers that would easily receive an AOS Award of Merit (or higher!) if brought to a table of judges. So many of the flowers we encountered were flat with wide sepals and petals. High- quality examples of C. nobilior f. amaliae in cultivation are known for producing light pink to white flowers with prominent stripes on the lip. Seeing show-quality plants in the wild is truly amazing, and not many species come from wild stock that seems to fit perfectly into “ideal” judging criteria (i.e., full, flat and round). Miranda got some amazing drone footage of these quality flowers located 30 or more feet (9m) in the air.

[8] Cattleya nobilior f. amaliae is just opening up. Note the enormous root system radiating out in every direction. A large root system is critical for success in such a hostile environment.

[9] A truly stunning example of this species that might garner an AOS quality award if it were presented to a judging team in the United States.

We hopped one of the fences surrounding a cattle pasture, and Stephen asked Francsico if anyone would be upset that we were doing so. After all, going through fences in Texas can be hazardous to one’s health! He mentioned that the locals were very friendly and would likely only want to know what we were looking at so intently. Still, we were careful not to jump a fence if someone was nearby so as not to show disrespect. As we explored the area, Mauricio (our orchid “eagle eye” who could seemingly spot orchids in trees a quarter mile [0.4 km] away!) ventured on ahead of us to see if more plants were obvious from the road. The rest of us got tired and decided it was time to head back, though where was Mauricio? We drove up and down the road for a while and even sent the drone to look for him. As the sun was dropping on the horizon, we wondered what happened to our companion. Considering we had no cell signal and were in the middle of nowhere, losing someone becomes a potentially dangerous situation! After about an hour, a tall, lanky figure appeared on the horizon and appeared to glide out of the sunset to walk down the hill toward our car. He was back and wondered why we had not driven down the road to pick him up! Mauricio’s long gait had taken him farther down the road than we had driven in the car while searching for him. Of course, he had found many additional C. nobilior f. amaliae plants in the trees ahead. We had an amazing sunset in the bush and returned to our hotel to eat the incredible Brazilian food in town. We planned to return in the morning and look for the plants that Mauricio had found on his walkabout.

[10] Constant brushfires create amazing sunsets. Stephen Van Kampen-Lewis (left) next to Chris Maupin (right).

[11] Chris Maupin gets a whiff of a low-growing flower.

The next day, we returned to the same cattle pastures that had yielded so many C. nobilior f. amaliae to expand our investigation and locate some more new locations for the species. We entered a forest next to the cattle pastures that looked like good habitat. We found some additional C. nobilior f. amaliae, including some that were at eye level. We also encountered more Cyrt. saintlegerianum and an unknown Catasetum species with a nearly fist-sized seed capsule forming. Additionally, there was a diverse assortment of blooming plants in the area that were not orchids, including Justicia, Jacaranda, Hippeastrum and Hadroanthus (Tabebuia).

[12] Cattle pastures often provide excellent habitat for Cattleya nobilior f. amaliae host trees. Chris Maupin (foreground) and Mauricio Verboonen walk out to investigate a tree covered in the target species.

[13] Telephoto lenses can be important when fully assessing the number of Cattleya nobilior f. amaliae on a tall tree. How many blooming plants do you see?

One of the more interesting experiences included having lunch next to two of the few Tabebuia trees that were clearly very, very old and had somehow escaped being harvested for their extremely dense wood. These trees were easily 70 feet (21 m) tall and probably just as wide; truly stunning specimens. However, the most interesting observation was that one tree had many C. nobilior f. amaliae and the other had none. These trees were well-spaced but still close enough to have several large branches crossing into each other’s canopies. Why would one of these have large, very mature C. nobilior f. amaliae and not the other? Their proximity means that the seeds are almost certainly traveling from the occupied tree to the unoccupied tree, but only one of them is suitable as a host. We can only speculate, but perhaps different mycorrhizal communities are present on the two trees, with only one community sufficient for orchid use. Dr. Maupin pointed out the possible role of average prevailing wind direction during the season when seeds are most likely to be dispersed. Of course, this speculation only leads to more questions, such as why two trees in proximity to one another and presumably of the same species have different mycorrhizal communities living on them? Maybe we will never really know the answer, but this conundrum certainly led to some lively discussions as we ate lunch.

[14] Another excellent example of the target species showing off its colors and a dehisced seed capsule.

The next day, we drove back to Brasilia to drop off Mauricio so that he could catch a flight back to his home near Rio de Janeiro. Of course, we ended up taking a few detours to find additional C. nobilior f. amaliae and got a handful of new locations to revisit in subsequent trips. One of these detours included visiting a monstrous cave called Lapa Terra Ronca within a state park called Parque Estadual de Terra Ronca. This cave entrance is over 300 feet (91.4 m) tall and 100 feet (30.5 m) wide, with a river that plunges into it from the outside. Lapa Terra Ronca had macaws and parakeets roosting in the ceiling, and the area would likely have yielded orchids if we had searched for them. However, we needed to get Mauricio to the airport and then get to our next destination, a few days’ drive from Brasilia. Diamantina, founded by the Portuguese in 1713 and a UNESCO World Heritage Site, would serve as our home base for the next leg of our adventure as we searched for rupiculous cattleyas.

[15] The colors on some of these flowers can be quite intense, as seen on a branch about 30 feet (9.2 m) above the ground.

[16] An unidentified leafless Catasetum with a nearly mature seed capsule in the foreground.

— Stephen Van Kampen-Lewis started growing orchids around 1992 at approximately 12 years of age. He has grown orchids in Canada, Arizona, Hawaii and Texas. He is a fully accredited AOS judge and is also the Chair of the Alamo Judging Center (San Antonio). Van Kampen-Lewis has created a YouTube channel (@SVKLOrchids) in which he discusses tips and tricks for growing cattleyas, catasetums and a few other genera. He enjoys growing his orchids outside in a shade house during the summer and also has some of the tricky cattleya species in an IKEA cabinet, all near Boerne, Texas.

—Francisco Miranda was born in Rio de Janeiro and began his taxonomic studies of the orchid family in 1981 while living in Manaus, Brazil, studying Amazonian orchids. In 1985, he left the Amazon and began field trips to Minas Gerais and Espírito Santo to find rupiculous Cattleya species in their natural habitats. Subsequently, he prepared hundreds of herbarium specimens and described many new species, mostly in the genus Catasetum and Mormodes. In 1987, he finished his master’s degree and continued to make frequent field trips to the habitats of the Brazilian cattleyas. Since 2001, he has been a qualified Taxonomic Authority for the AOS, specializing in the determination of Brazilian orchids, mainly cattleyas. Presently, he owns Miranda Orchids in Haines City, Florida, where high-quality species of cattleyas are being produced. He gives lectures throughout the United States, Canada and also in Brazil. More recently he resumed his taxonomic work and is guiding tours to Brazil for orchid observation, photography and conservation awareness.

—Dr. Christopher Maupin is a research scientist based in Houston, Texas, where he works in the realms of paleoclimate, isotope geochemistry and severe weather. His great-grandfather, Francis King, founded an orchid nursery in Bristol, Rhode Island, during the first decade of the 1900s, operating it for most of that century. When Dr. Maupin’s grandfather moved to Florida after serving in WWII, he relocated a backyard’s worth of cattleyas there from the family nursery to his new home state. Orchids, consequently, have always been a significant part of Dr. Maupin’s life as a native Floridian. Through the past two decades, he has, with equal interest, collected Brazilian bifoliate species and relevant scientific and historical information about their habitats, life histories and climatological preferences.

References

Lima, L.H. 2004. Noble Cattleya – The Bifoliate Cattleya nobilior Lives Up to Its Name. Orchids

73(11):830–833.

Miranda, F.E. 1995. Orchids’ Map Over the Continent: From the Coast Across the Mountains, Deep into the Savanna. In Brazilian Orchids edited by Teruji Shira- sawa. Sodo Publishing: Tokyo, Japan.