LAST MONTH'S COLUMN discussed the general physiological and environmental triggers that bring plants into bloom. By way of review, there are two components to making a plant bloom. The first is physiological. Is my plant mature enough to bloom? Is it large enough to have built up reproductive reserve energy? Does it have a sufficiently good root system to facilitate nutrient absorption? The second component to good blooming is a collection of environmental factors that specific plants use to determine when to flower. The most common include diurnal variation between day and night temperatures, absolute day and night temperatures, seasonal variation in day length, seasonal variation in light levels and seasonal variations in water availability.

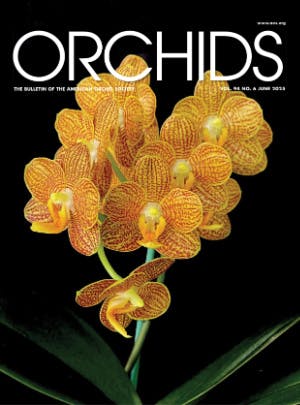

[1] Phalaenopsis, such as this Phalaenopsis Plantation Anticipation ‘Orchid Konnection’ AM/AOS (grower: Orchid Konnection), is derived from species that strongly depend on temperature variation to induce flowering

Now let us look at specific genera. The genus Phalaenopsis is a good place to begin. Not only are they fairly easy to understand, almost everybody grows at least a few of them. Depending on the species or hybrid line, there are generally three main triggers involved.

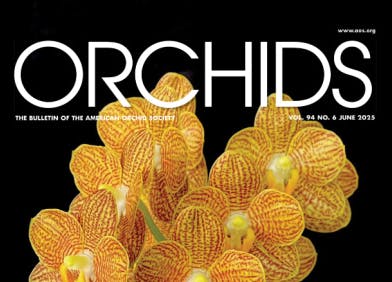

[2] Phalaenopsis LD’s Bear Queen ‘Limey’ AM/AOS (grower: Pat van Adrichem). The species and hybrids in the background of this group of Phalaenopsis are not dependent on temperature variation and tend to flower whenever there is warmth and bright light.

LARGE-FLOWERED GROUP Breeding lines that typically produce long, arched stems of multiple, large, flat flowers are dominated by three species in their background: amabilis, aphrodite and schilleriana. These species (and most of the others in these hybrid lines) are completely dependent on temperature to trigger flowering. You see them in flower in the mass market year-round because they are forced into bloom just like poinsettias. They are so dependent on temperature that the mass producers have algorithms that allow them to precisely control the time from chilling to first flower open, allowing them to meet changes in market demand. These plants are brought into flowering by a combination of absolute night temperatures and reduced day temperatures that mimic those in the species’ natural habitat. This group of Phalaenopsis naturally flower in the winter and spring following a period of day temperatures below about 84 F (28.8 C) or lower and night temperatures 15–20 F (8.3–11.1 C) lower. If temperatures rise above the low 80s F (27–28.8 C) during the daytime, inflorescence development may stop, and if night temperatures exceed the mid-70s F (23.3–24.4 C), inflorescences may not initiate. If you have difficulty flowering these phalaenopsis, give them cool conditions in the fall until you see flower spikes developing.

[3] Graphical representation of the day-night temperature differential for two species in this group of Phalaenopsis. Flower initiation begins in the fall as the temperature difference exceeds 15 F (8.3 C).

A word of advice regarding Phalaenopsis schilleriana and cool temperatures. Although this species requires conditions described previously, it is less tolerant than the others in the group and may defoliate if exposed to night temperatures below about 60 F (15.5 C). When this happens, the foliage will take on a reddish hue, eventually yellowing before dropping off. The plants themselves will recover if not too badly damaged.

[4] Graphical representation of the number of clear days in each month in the habitat of Phalaenopsis bellina.

NOVELTY PHALAENOPSIS This group includes species such as violacea, bellina, amboinensis, lueddemanniana and their hybrid lines. These plants tend to produce shorter inflorescences, often branched, carrying few flowers at a time. They are not at all dependent on temperatures to flower and, in fact, often flower during the warm summer months, and large plants can flower year-round. They appear to be brought into flower by a combination of warm temperatures and bright light, although the species and simple hybrids may be somewhat dependent on seasonal day length. Give these novelty phalaenopsis light and warmth, and they will flower when they have sufficient reserves to do so.

[5] Phalaenopsis lobbii ‘Fajen’s Hat-trick’ AM/AOS (grower: Fajen’s Orchids). This third group of Phalaenopsis a native to habitats that experience cool to cold, dry winters and may become deciduous.

DRY WINTER REST The third group of Phalaenopsis, also considered to be novelties, is much smaller than the others. This group includes species such as lobbii, parishii, wilsonii, taenilis and appendiculata. These species are found in seasonally dry climates of northern India, Burma, Thailand, northern Laos and Vietnam and southern China, and can be deciduous if kept sufficiently cool and dry during the winter. Plants need a decidedly cool, dry winter rest and usually flower during the dry season from November to February or March. Their habitat can be exceptionally dry and cool. For example, the habitat of Phal. lobbii experiences a period of four months (November– February) when rainfall never exceeds 0.5 inch (12.7 mm) per month. Compare that to July and August when rainfall exceeds 32 inches (81.3 cm)! During that same November–February period, daytime temperatures average 71–79 F (21.7–26.1 C) and nights can average as low as 47 F (8.3C), not exactly what we think of as Phalaenopsis conditions.

[6] Graphical representation of the temperatures and rainfall by month in the habitat of Phal. lobbii. Note how cool and dry winter is on average.

Next month, Cymbidium triggers.

— Ron McHatton, AOS Chief Education and Science Officer (email: rmchatton@aos.org).